Live Makkah

Live Madinah

Urdu Font Download

Latest News:

Padubidri: Fishing boat capsizes; all 7 fishermen on board rescued Alleged atrocity on lawyer: Punjalakatte SI suspended Moral policing at jewellery shop: 4 arrested Bajrang Dal activists try to assault youth, girlfriend in Mangaluru SC to hear Bilkis Bano’s plea against release of 11 convicts on 13 Dec Nusrat Noor: First Muslim Woman to Top Jharkhand Public Service Commission

Latest News:

Padubidri: Fishing boat capsizes; all 7 fishermen on board rescued Alleged atrocity on lawyer: Punjalakatte SI suspended Moral policing at jewellery shop: 4 arrested Bajrang Dal activists try to assault youth, girlfriend in Mangaluru SC to hear Bilkis Bano’s plea against release of 11 convicts on 13 Dec Nusrat Noor: First Muslim Woman to Top Jharkhand Public Service Commission

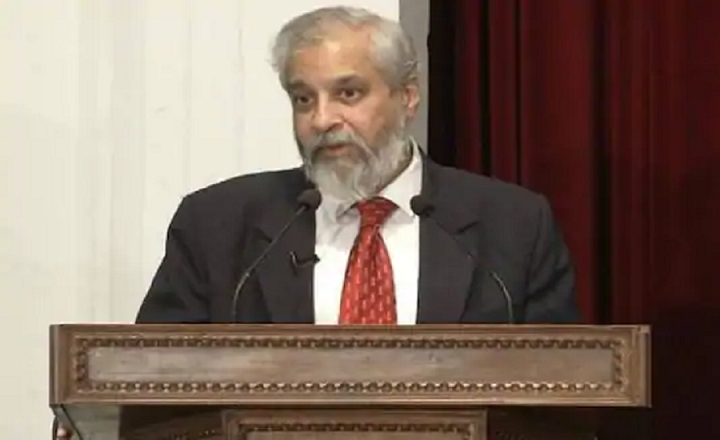

Time for Parliament to Enact Law on Hate Speech: Justice Madan Lokur

New Delhi, 21 Feb 2022 [Fik/News Sources]: With election swansong underway and in the backdrop spike in unbridled hate crimes against minority communities, particularly Muslims, former Supreme Court judge Justice Madan Lokar pitched for enactment of law against hate speech by Parliament in accordance with United Nation’s convention on genocide.

Citing the example of recent religious assembly ironically styled as “Dharma Sansad” in Haridwar where calls for ethnic cleansing or genocide of Muslims was made, the retired judge, who is now emerging as prominent voice in civil society circles, said it was time to build a public opinion and have a law, get down to action.

“We just need to think about it. We need to make sure Parliament enacts a law on hate speech,” he said while speaking at an event on the subject of “Hate Speech in India” on Sunday.

He began his address by saying that there was no legal definition of hate speech in India even as the 1969 amendment of the Indian Penal Code introduced the concept of hate speech in the legal books through section 153. This section of IPC is used against persons who indulge in promoting disharmony, enmity or feelings of hatred between different groups on the grounds of religion, race, place of birth, residence, language, etc.

He then mentioned section 505 of the IPC which deals with statements provoking public mischief.

These provisions in the law, justice Lokar said, are used to deal with hate speech.

He dwelt at length on Representation of the People (RPA) Act to explain how politicians taking part in elections get away with hate speeches. He recalled in 1999-2000, a committee was set up to review the working of the Constitution recommended that punishment should be mandatory against politicians fighting elections who make such speeches. The committee had asked for disqualification if the candidate himself or his election agent tried to bring about disharmony.

“It is one thing for a candidate to say I did not say anything. But if somebody at your instance tries to bring about hatred, then the candidate is responsible,” said Justice Lokar.

He also cited several cases where the Supreme Court gave “broad interpretation” of hate speech or attempt to hate speech. For instance, the case of Pravasi Bhalai Sangathan v UOI, Justice Lokur, dealt with hate speech in great detail. “The Supreme Court looked at hate speech as something having the effect of delegitimising, marginalising people belonging to a group and beyond causing distress,” he said. “What is important in this, there is no mention of violence. Because even the IPC doesn’t talk about violence.”

The case, according to Justice Lokur, shows how “hate speech lays the groundwork for later, broad attacks on the vulnerable that can range from discrimination, to ostracism, segregation, deportation, violence and, in the most extreme cases, to genocide.”

It was in this case that the Supreme Court asked the Law Commission to look into this entire aspect and give a report.

But, Justice Lokur lamented that the troubling aspect is, nothing has happened. The report has been shelved and the law commission doesn’t have a chairman for the last couple of years, he said.

He discussed the report which gave examples of countries and how they look at hate speech problems. “Canada looks at it from the standpoint of a reasonable person. What is a reasonable person? ….Is a minister who gives hate speech a reasonable person? A minister who puts a garland on persons who are convicted of lynching. Is he a reasonable person?’ he asked.

“If these are reasonable persons, then reasonableness has a completely different meaning from what at least I understood as a student of law.”

Further examining the Canadian jurisprudence, Justice Lokur said that the hate speech has a chilling effect on targeted groups.

He said in all these countries cited in the report the important point is, violence is not necessarily a consequence of hate speech.

He was also critical of how courts have dealt with hate speech cases stating he was sorry to say that courts in India have tried to bring about the concept of violence into hate speech.

Citing the example of Sulli Deals and Bulli Bhai auctioning of Muslim women, he said there’s no violence in this, but is it not hate speech? “Can you say, “It’s okay! Freedom of expression.”

He also cited the slogans raised by a BJP minister during Delhi election: “Goli Maaro…”

“What is that, if not incitement to kill? So, these are things that have been happening in the recent past. How have courts reacted to it?”

He said In the Amish Devgan case the Supreme Court said that hate speech was punishable as an incitement of violence. Calling the court’s view as retrograde, he said, “Violence was never a part of hate speech in spite of the earlier decision and the report of the Law Commission.”

“Article 5 of the genocide convention says that the contracting parties undertake to enact legislation. We’ve not enacted any legislation,” he said.

He, however, hailed the apex court whose intervention to protect critical speech by quashing FIR against a journalist in Meghalaya, Patricia Mukhim, while at same time ensured action against monks who made hate speeches at the infamous “Dharam Sansad”.

He said the actions of the government or lack of it shows “you have a certain acceptance that hate speech is okay. Prosecution or the state is going to be silent spectators. I’m not alleging conspiracy, but we’re just going to keep silent about it.”

“We have to persuade courts to be far more proactive,” he said.

Prayer Timings

| Fajr | فجر | |

| Dhuhr | الظهر | |

| Asr | أسر | |

| Maghrib | مغرب | |

| Isha | عشا |